Video Games: The State of the Field

A discussion with Steve Mamber, Peter Lunenfeld, and Eddo Stern.

LINKS AND DOWNLOADS

DATE

2012CONTEXT

MEDIUM

PEOPLE

(originally posted in the Winter 2012 issue of Mediascape)

Introduction

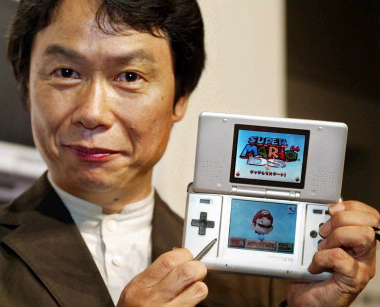

Within the last decade, video games have emerged as a leading industrial and economic force, as a locus of cultural identity and exchange, as a site of great experimentation and proliferation, and as a subject of intense intellectual interest. The United States alone boasts some 183 million active gamers, and the billions of dollars and hours going into video game development and play only begin to describe the impact of video games on culture. To help describe the current moment in video gaming and to explore various related issues, Mediascape asked Cinema and Media Studies doctoral candidate David O’Grady to hold a roundtable discussion with some of UCLA’s leading digital media scholars: professors Peter Lunenfeld, Steve Mamber, and Eddo Stern. It seems fitting that this discussion about the current state of video gaming was held the day after the release of Nintendo’s 3DS handheld device, which now brings a 3D display to gaming without the use of special glasses.

A special thank you to Andy Myers for transcribing the discussion, and to Meta editors Jim Fleury and Ross Lenihan for arranging it.

Discussion

David O’Grady: Video games seem to be coming into their own at this particular moment. Tom Bissel in Extra Lives describes this as a “Golden Age” of video gaming. Certainly such pronouncements are easy to make. I’m wondering to what degree you think this is true, and if so, what’s driving this cultural moment? Is it the proliferation of different platforms and interfaces, the style and varieties of gaming that are available today? Is there any sort of working thesis we might attempt to advance for “why video games now?”

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CZZbzthHtUM&w=560&h=315]

Eddo Stern: The same term has been used in the past. “The Golden Age” of video games usually refers to the arcade game era, when arcades were as ubiquitous as movie theaters. It’s interesting how that incarnation of gaming has come to pass.

Regarding the question of our current “Golden Age,” there certainly have been big shifts in terms of the diversity of game types, the amount of people playing them and the de-stigmatization of the “Gamer” label. Games are no longer solely identified with teenage (and twenty-something) boys.

Peter Lunenfeld: I think it’s really dangerous to invoke “Golden Ages,” in large measure because they’re usually driven by a certain kind of “fanboyishness” that masquerades as criticality. And when you think about “Golden Ages” of other popular media, like comic books, you don’t necessarily want to claim a “Golden Age,” because your “Silver Age” is coming right at you then, which is when you begin to lose your audience, as the history of comic books shows.

Eddo Stern: Aren’t “Golden Ages” usually applied backwards in time?

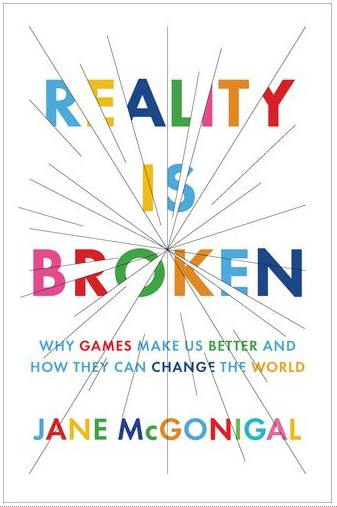

Peter Lunenfeld: Yeah, it’s a nostalgic thing. When Jack Kirby was first doing Captain America, he wasn’t sitting around on Seventh Avenue going, “It’s the Golden Age, damn it!” No, he was saying, like, “I’ve got to feed my kids and I’m gonna crank out another piece of popular culture that people love.” And so I do have a concern about the kind of critical literature about gaming that seems to be completely imbricated with the desire to see gaming triumph in some way. It’s already a multi-billion dollar industry. I’ve never understood Henry Jenkins’ desire to push this. I understand Jane McGonigal a little bit more because she’s at least in the industry. I’m mostly interested in theories of theories of video games because I don’t play video games. So I have a meta-meta approach to this dialogue, and I’m probably going to be the least enthusiastic member of this sort-of-rounded-off-table.

Steve Mamber: On the side of enthusiasm, I see a number of very encouraging signs. Whether or not it’s a “Golden Age,” there are very interesting developments. I think particularly the breakup of dominance of the platforms is a very significant thing. What started with the Wii has really been increasing, and I think it is a big deal that casual gaming has reached the extent that it has. Also, the proliferation of portable devices has led to so much interest in gaming that we can kind of get past the sense of dominance of certain kinds of gaming. So I would see those developments as a really big deal—and I’m sure we’ll talk about this kind of stuff more as we go along. For example, note how quickly the Kinect went open source, or that Sony, which has not been on this side of things very often, is announcing (at least) an SDK [software development kit] for the Move, and the things that used to just be in the hands of developers are in the hands of everybody. I think it’s really important that universities are making games, and people like Eddo are running very successful labs and doing courses where games are being produced, and that video game theory courses are proliferating. So, I think it’s a set of interesting, helpful signs. What it all amounts to is still very much open for debate, but there’s a lot of good stuff going on.

Peter Lunenfeld: I think that you can look at this as an expansion. We’re contextualizing and situating this discussion within a school of theater and film, that then became a school of theater, film and television, that then became a school of theater, film, television and digital media. That kind of expansion alone would indicate that this is part of a historical progression that goes back fifty or more years to the incorporation of thinking about certain kinds of audio-visual media within the academy, in graduate programs, both film MFA programs and also art MFA programs that started to expand to look at other media forms. These expanded in the 1970s, when you get avant-garde filmmakers going off and literally supporting themselves via a circuit… and documentary filmmakers to a certain extent too, right? Steve would know more about this, the 60s and 70s generations of structuralists and cinéma vérité documentarians who would situate themselves within making programs at universities, then you saw media artists do that, and now I think you’re seeing a certain kind of game maker/game thinker extending through the academy. And then each of these successive waves reacting in turn to heightened student interest. I think it would be almost impossible to found a new program to study cinema, and only cinema, in 2011, anywhere. You couldn’t get a dean to support it, but I think you could absolutely get somebody to support either television studies or game studies.

David O’Grady: We’ll circle back to the role of the academy; it’s where I think we’ll arrive at the end of this conversation. So let’s move on to the next topic, one I call “the Roger Ebert provocation.” As cinema encountered a century ago, the move of any new cultural form into the mainstream encounters resistance from various quarters. Often this resistance hinges on questions of cultural legitimacy and manifests as debates about the nature of art. Roger Ebert reignited such a debate last year by publicly rejecting video games as art. Advocates of games responded by posting examples on Ebert’s blog, including Eddo’s video game Waco Resurrection. Is the question of games as art a necessary or useful subject for developers and/or researchers in order to advance the field culturally and intellectually?

Eddo Stern: It certainly comes up a lot and is now a beaten horse. People who can really speak to the question often choose not to because the premise for the debate is generally naïve and has become debased. The debate often circulates around a simplistic idea of high-versus-low, that somehow art is high culture, and games are low culture. The debate follows the lines of “How are we going to convince people who doubt games that games are high culture?” Who are the arbiters of taste in this arena is a big question. Are they game developers, game players, theatergoers, gallery artists, or film critics? Someone like Roger Ebert, who hasn’t played any of the games that he writes about, is certainly not the person who should be talking authoritatively about this question. But one thing that’s useful for me in regards to this question is thinking about different media along a continuum with car design on one end—something very functional in design but also aesthetic—and a form like poetry on the other end. It is then useful to ask where games fall along this range. Specifically, what role do functional constraints play in the “art” of making a game? Just as aerodynamics and engineering constrain how you design a car visually and performance-wise, in games we can identify fun, action and balance as examples of inherent qualities of the medium that constrain game design. We quickly enter the more murky territory of design versus art.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UXhoh2yE6bI&w=560&h=315]

Part of the problem I have is that work labeled by art world terms as “game art” is very different from arty games or games that are artistic labeled as “art games” by the game world. You could define “game art” as works made by individuals who are more established as fine artists in a more traditional sense—artists who exhibit in fine art spaces and have taken on games as “found objects” and spun them in various conceptual and aesthetic ways, where the constraints needed to make a “well designed and playable game” are broken. The breaking of the constraints of design often make these works more palatable and familiar as works of “art” in line with current practice and discourse. Examine JODI’s minimalist games, games stripped of all recognizable iconography and you’re likely to comment, “Oh, it’s a piece of minimalism.” Or Tom Betts’ QQQ, a game hack that uses a glitch in rendering to make an aesthetic gesture appear as an expressionistic work, generated by a line of code executed by a machine. His work may invoke thoughts of abstract expressionist painting or Dadaistic performance. These are examples of artists playing with games as raw material.

So coming back to the “Can games be art” debate, which has been centered around the question of whether we can look at a mainstream, successful game and talk about it as art. This is a tricky question that quickly leads to the perilous territory of defining art. More tangibly, perhaps, the question reveals one of the creative challenges of game design—how to create an experience that simultaneously delivers a critical point of view while creating what most gamers would call a well designed game—something most gamers would label as “fun.”

There are a few game designers/artists like Tale of Tales – creators of The Path and The Graveyard – or MolleIndustria – creator of the McDonald’s Video Game – who have navigated through the challenges of making games that offer critical distance to the medium while preserving the integrity of gameplay. For example, MolleIndustriaoftenplaces the player in a position of ironic identification—allowing the player the play the antagonist as a method of exposing apparatus of power through the logic of gameplay. This use of irony as a method to allow game logic to stand in for a corporate logic of “winning” is both effective and creative, and allows the critical games of MolleIndustriato reflect on our culture while preserving the inherent qualities of the game medium.

There are many other challenges that make games a difficult medium of artistic expression—and often force the hand of artists to undermine the inherent properties of gaming. Game logic lends itself to competition and action—games come with their own built-in genres that are hard to wiggle around. How do you make an action movie out of Jane Eyre? How do you make a non-action game? It doesn’t quite work as game, though it might as an artistic comment on games….

Peter Lunenfeld: You add zombies.

Steve Mamber: You’re raising great questions, of course. It’s always funny to me when film people find another entertainment activity as disreputable, because of course they’re coming from a medium that suffered that same history, but now I guess the academic battle’s been won. Television has gone through the same thing. It’s like the next thing everybody can dump on as being not at the high level of these media that have now been accepted by academia. I guess one parallel that’s worth trying to kick around a little bit: how much you could see Electronic Arts and Sony and other big game makers as the equivalent of Hollywood. And I think what Eddo is very usefully raising is the idea of to what extent can there be an independent gaming industry with its own history, and own aesthetic, and own sense of connections to art forms that aren’t ruled by the dominant form. And that’s where, again, I think the platform breakup is a very useful thing, because if we use as our aesthetic standard the $60 PlayStation or Xbox game that everybody has to conform to, we’re going to be in huge trouble because we’re never going to be able to compete with that. But a phenomenon of digital media that Lev Manovich and others of course have recognized is that the consumers want to become producers very quickly. I think video games are very much in that path, and it’s very important to find the tools that people can use, but also recognize that there are X-million casual flash games that people are constructing and putting online; there are websites all over the place where people are producing and consuming games. So it’s sort of a let’s look at the YouTubes of video games rather than the Columbias and Warner Brothers of video games. Let’s look at how people are producing and consuming together what’s coming out and what kind of aesthetic is possible there.

ZOMBIES VIDEO

Peter Lunenfeld: I’m the person Steve was talking about, the one drawing that line. The argument about art is, as Eddo says, a pointless one. Much of what we’re talking about are issues of making, and issues of design. One of the things that I find to be intriguing is serial interaction. I’ve watched Stagecoach maybe seven times, eight times, at different stages of my life, in the same way that I’ve read Lucky Jim by Kingsley Amis perhaps ten times. I’ve done almost none of that consciously with television. Television just comes on and I’ll watch something that I watched twenty years ago because it’s still on, but it’s not something I’ve gone out to find. I could never imagine watching 24 again—I can’t imagine devoting twenty-four hours to watching 24. And so one of the questions that I have about this discussion about gaming is precisely: are games the source of experiences that one returns to at different stages of one’s life, the same object that one wishes to contemplate over and over again? One of the things that Jane McGonigal talks about in Reality is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How they Can Change the World is that a game is designed to get you to engage with it—and, once you’re done—you then move on to the next game. It’s not something that you necessarily return to.

Eddo Stern: This thinking applies only in the mainstream, dominant genre of gaming. I mean, take chess for example, or take any multiplayer video game, and player engagement works very differently. You grow as your opponent grows, you develop more strategy over years of play.

Peter Lunenfeld: But a chess game is something one studies to become a better player —

Eddo Stern: — Same with Starcraft. Starcraft has basically existed in the same, almost identical structure for almost fourteen years now, and there are people whose lives are built around it, people keep coming to Starcraft—

Peter Lunenfeld: —But chess is artful. A chess game is not an artwork.

Eddo Stern: The chess game as a rule set or an object, or a particular game of chess played at a specific time and place?

Peter Lunenfeld: The playing of that game—

Eddo Stern: —The system or the particular set of exchanges?

Peter Lunenfeld: On the other hand, the Star Wars chess game, that’s some fine art.

Eddo Stern: It gets complicated because some games are very much a system of play, in which case we’re just now hitting that point that we should distinguish the performance of the game as performed by the players from the game as a system for play. You could look at certain specific chess games and say, “Wow, that was something special”—

Peter Lunenfeld: —Artful, but not “artlike.”

Eddo Stern: A basketball court is a place where amazing art could happen. Acrobatics, dance, ballet… that kind of art. And you could say the same for chess. But the creator of the system, the person who invented basketball invented a certain set of constraints—designed experience that then produced certain performances. Same with opera, let’s say. Here someone created a structure for opera, and then the performance within that was artistic. Or acting—the same play being done over and over on Broadway, and then a certain actor is putting forth an amazing performance…. It’s an interesting question here of space for the players themselves as artists—are they allowed to be creative as actors or not?

Peter Lunenfeld: It’s also something that I see playing out, again, within the university context all the time, that if you can say what you’re doing is art, you can justify funds and grants. Or you can say it’s science. Whereas with engineering or design, it becomes more complicated.

Eddo Stern: I just want to follow up on something Steve was saying about the tools and the platforms. I’m actually probably less optimistic about them, maybe, than you are. You made a great point about breaking away from the standards that are established by corporations who have a very clear financial goal. This is going to be a $60 object, it’s going to take this much time to play it, and it’s therefore probably very expendable by design (to your point, Peter). Okay, I bought my chess set, I’m done, how am I going to feed that industry? Also, take the joystick here, it’s a standardized piece of hardware, the games now must involve this kind of lateral movement. The Wii—oh, now you’re swinging your arms around. All of these examples are constraints, and they narrow the field of possibilities, they narrow the imagination.

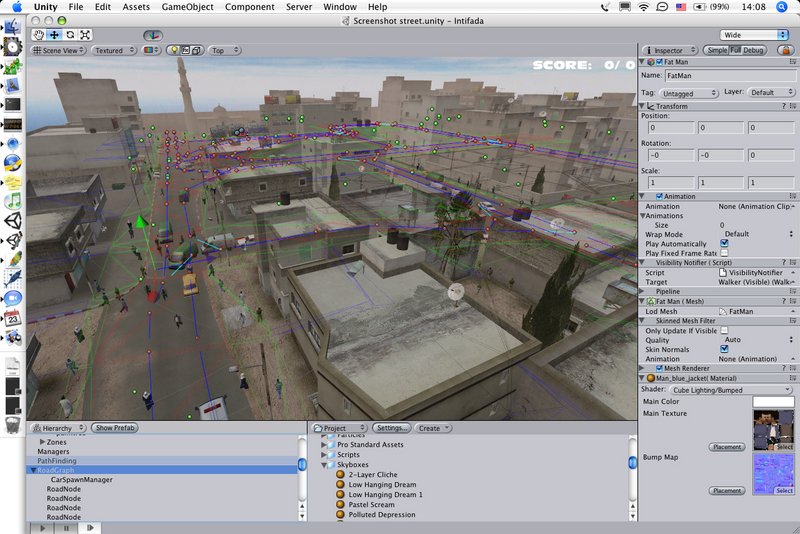

A second point I wanted to make is in regards to the development tools that are given to the game playing “audience” to produce games for certain platforms and devices. I’m quite suspicious about that, because having gone through the Xbox developer cycle, it’s very cynical the way it’s designed. Indie developers are given a false sense of agency seemingly participating in the “big time,” making a console game! But the reality is that the console makers are in control: you’re not allowed to modify any hardware; approval to get games released still comes from Microsoft, Sony and Nintendo (and now Apple). Even game engines tools like Unity3D, which is more open and free, inherit too many of the game industry’s conventions.

Unity is expecting to import animations and 3D models from Maya that are structurally based on a humanoid walk cycle. Well, what if I don’t want a humanoid? Oh, now it’s really tricky. The engine is based on a first-person perspective; the camera is set by default to be at eye-level. Oh, I need to change it. Oh, no, you can’t…. Still, I think the creative voice in game design is motivated by a struggle against what is trickling down from the mainstream industry because the industry still determines the tools and the standards.

Steve Mamber: Well, that’s where video games are following the same path as film and television and other media: they’ve had these same kinds of constraints, so hopefully one of the paths here is one of media literacy, and that as you’re using new tools, you’re seeing the limitations of them, and hopefully that can lead to breaking out of it. People in art programs and media programs don’t necessarily want to become professional programmers, or they don’t want to be full-time game developers. Instead, the idea is that the tools eventually will be ones they’re comfortable enough with, that they’ll have some effect on how they’re used. I think in film there isn’t that same kind of feeling of constraint because it’s a little bit further along on the path. People don’t pick up a camera and say, “This is forcing me to make a certain kind of movie,” whereas I would agree with Eddo: Unity makes you feel like there are only certain kinds of games you can readily make.

David O’Grady: The games-as-art debate is joined by other efforts to reframe games as socially, culturally, or cognitively valuable. Returning to Jane McGonigal, she contends that video games can help us actually solve real-world problems, like poverty and hunger. Steven Johnson has advanced cognitive arguments in favor of gaming. And, of course, the whole marketing pitch of the Wii is based on a two-fold, feel-good strategy: gestural gaming is good for family togetherness, and it’s good for physical fitness. All of this serves as a preamble to a fundamental question: Why can’t games just be games? Why do we need to attach some other benefit to games in order to legitimize them?

Eddo Stern: That’s a really good question. I feel like if you look at other forms of so-called “superfluous” or “leisure” activity, they are seen as products of a society that has too much free time on its hands. You can put all kinds of things, like fashion and, you know, food obsession and golf and things like that, into this category. Sure, people will talk about sports, “Oh, they’re good for exercise,” but digital gaming is still the scapegoat of real world violence, and the need to legitimize games as useful is motivated by their stigmatization.

Peter Lunenfeld: — Columbine —

Eddo Stern: The debate around the social values of games has become a bit silly of late. On the other hand, it’s been interesting to consider that if we accept that playing a game can turn you into a Columbine killer, or save the planet—this is already saying a lot about what a game is as an art form. The idea that this audio-visual experience can transform you in such a way to make you act out violently, that’s already a radical statement about the power of the form. So, I feel like adding weight to both sides of that debate is, in a way, enriching the discussion about games.

Peter Lunenfeld: My favorite magazine ad for television in the 1950s offered a tag line saying, “Be a Magellan in your living room,” which is exactly the same kind of pro-social messaging about media. If you look at the way television was sold, part of the pitch was that you could not live without TV if you expected your children to be modern. That same positioning is there with video gaming, too. I want to return to the idea of game studies and its positioning within the university. You have to look at the infrastructures and foundations that will fund research. They have a pro-social edutainment model that they will follow for as long possible.

In the Design Media Arts program at UCLA, we are asked regularly by our development officers, “How come you guys don’t do that stuff that we read about that gets funding all the time?” And we respond, “’Cause we don’t—we’re the anti-social guys.” No, I honestly feel that there are certain things, such as art, that can at least engender a certain amount of respect and lead to funding sources. If you can say, “I do art that does good,” that’s a whole new spigot. That said, I do think that there are ways to build in really interesting multivalent modes of communication. I am interested in social gaming’s relationship to communications, especially the game Scrabble. Mothers and daughters will play Scrabble online, use it as a way to kind of check in, to talk to each other without having to talk directly. One piece of parenting advice is that the easiest time to talk to your kid is when you’re driving them somewhere, because you’re actually not looking directly in their eyes—there’s something else going on, and so you can actually raise complex issues, and I think that there’s nothing wrong with saying that’s part of what makes gaming pleasurable. It’s that it keeps us from the intensity of the direct eye-to-eye contact, which personally, as an academic, I find exhausting after 30-40 seconds. [Laughter.] When I say, “How you doin’ today?” I don’t mean it. I don’t want to know.

Eddo Stern: It’s interesting, though, that the “games as art” and the “games have value” debates are pulling in very different directions as far as where games fit in culturally.

Peter Lunenfeld: But also of the least interest to the people making the most interesting work. That’s what I always say, that both of those issues are extrinsic questions to makers. That makers want to make interesting, compelling work, and sometimes that work is going to have a strong pro-social component, and sometimes it’s going to be art, and sometimes it’s going to be, what’s that, Robot Unicorn Wars, you know, which is just—

Eddo Stern: —Minus the “Wars.”

Peter Lunenfeld: Yeah, or Robot Unicorn Whatever-it-is.

Eddo Stern: Attack.

Peter Lunenfeld: I hadn’t quite realized that. But in aggregate, they’re a war. It’s a war against mortality.

David O’Grady: We’ve talked a little bit about technology, and I wanted to circle back to that conversation because it’s probably impossible to talk about video games without talking about the technological base for their existence, for their variation, and perhaps for their rigidity and constraint as well. Are there certain things going on now technologically—or recent historical antecedents—that are of particular industrial or theoretical interest?

Eddo Stern: One thing I think that has changed gaming tremendously from a technological perspective is networking. The fact that games now exist in a networked platform has made possible one of the genres that I find the most compelling as a gamer (and perhaps as a developer one day, although it’s a daunting genre): the massively multiplayer online game. The idea of a networked, immersive social space that is on 24/7, intercontinental, endless in scale and depth, but networked and constantly updated, and invigorated with live, real people as the actors—is radical. This obviously is not only manifested in gaming, but in a lot of other things we see now online. But networking is just one of many.

Steve Mamber: I’ll take maybe two or three, then, that excite me a lot that are very much of the moment. I think iPads are a very significant platform, and they really do change gaming, and it’s amazing all of the games that are interesting, fun, and involving on an iPad that are just too constrained on smaller devices. Also, the way that the screens can feel almost 3D-like leads us to another big development of the past week, and I think 3D without glasses is a very important thing.

I’ve always been fascinated by 3D anyway, and it’s an interesting phenomenon to look at with movies. It’s one of those places where movies and games get closer, but I think when you see a demo of the Nintendo 3DS it really does get exciting. But the question emerging is how open a platform is it going to be, and is it just going to be another vehicle for $40-$60 games that some company is producing and that aren’t being made by artists or universities, or elsewhere. Nintendo’s actually pushing this 3D platform not just for games, but whether it will expand beyond remains to be seen. The fact that there are all these devices that you can walk around with and still have very involving game experiences seems like a very important thing.

Then the other that seems absolutely huge and a real revolution are the interface shifts of the last few years, and Kinect and Move are really important changes. It started with the Wii, but there’s a world of difference between waving a wand around and walking into a room and having a game recognize that you’ve shown up. Now you can interact with the computer in this completely natural, non-joystick kind of way. So, again, I think it’s going to be a question of how open those platforms really are, but note how swiftly Kinect became this open-source device (e.g. Open Kinect). It’s absolutely amazing, and I think that it’s evidence of the huge appetite out there for people to interact in game-like ways with digital systems, but not in terms of traditional platform games. So, I think all of that is just a really big deal, and is going to change very much that sense where you have to be part of the club in order to get used to all the buttons and switches on a weird interface.

Peter Lunenfeld: I think this has a lot to do with ambience and ubiquity. That those two key user interface (UI) terms really become spread through society in a way that I wouldn’t have expected ten years ago. Running your hand underneath the automatic water spigot in the bathroom is actually an interactive experience. And if it is, what was once a UI experience becomes more a gaming experience in this weird way—this ubiquitous ambient technology is becoming much more about a kind of playfulness than a utility. That may be one of the things that I find most interesting about this moment in gaming. I’m interested in what Nick Montfort and Ian Bogost are doing with the platform studies, where they look at games not as a unique artifact to be analyzed, but instead they examine the game, the console, the marketing, the paratextuality of it all, and the interrelatedness of the experience that the user has with the capacities and capabilities of the developer, the marketers, and so on. I think that’s really, really important, and goes back in an interesting way to what apparatus theory was about early on, before it got completely hijacked by psychoanalytic theory. I’m thinking here of the dispositif as a systematic way of looking at the cinema that included the unconscious, but then become completely and utterly dominated by discussions of the unconscious.

David O’Grady: Much like film, video games can be authored by individuals, small groups, or by large teams working with a studio-like industry. Is it possible or productive to think about video games along auteur lines? And we might perhaps single out Will Wright, Sid Meier, and Shigeru Miyamoto as potential auteurs. We could also probably make the argument that Miyamoto is the embodiment of Nintendo’s studio style. So, then is the auteur as a concept a useful one for video games, either as a marketing conceit or as a critical tool for useful analysis?

Steve Mamber: A simple answer for me would be, ”Yes.” But the question is, what kind of auteur are we talking about? I think you could say Miyamoto, who, if you’re going on a traditional, film-wise concept of auteur, would be more like perhaps a David Selznick. But Miyamoto is a great artist, and his work is worthy of attention. I feel very much the same thing about Will Wright. Of course, as with auteurs in film, we can agree or disagree about names. The more important idea is whether or not creativity is possible within that environment. And it’s probably the case that it feels like Will Wright is constrained somewhat by his relationship to Electronic Arts and he would be doing much more interesting work if he didn’t feel like he had to sort of feed the commercial beast.

Eddo Stern: He sold his company to them.

David O’Grady: I feel that when playing Spore, for example.

Steve Mamber: But that’s an old story with film, so you know the names we probably want to invoke in terms of traditional auteurists would probably be like a Walt Disney or Selznick or somebody who kind of ran a studio as well as had considerable talent but maybe was more in evidence in their early days, and then later —

Eddo Stern: — Peter Molyneux, maybe?

Steve Mamber: Yeah, there are other names we could probably point to, but I think the idea that there are artists working in video games is one worth both defending and looking at. Will Wright is worth serious study, and students should be writing about him and looking at his games closely. To that extent, I think auteurism has proved itself in film in a way that video games could well emulate and not just call it an anonymous craft where who’s doing it doesn’t matter. There have been really great pioneers… and, like film, I think what’s probably most interesting is once you get past the big names is what the whole second tier would be. And it should just be part of the study of video games that there is a history, and there are people who’ve made great contributions—both in the creation of games and also in advancing the theory of video games. All of that should be studied.

Peter Lunenfeld: It’s interesting that you invoke Selznick. If there’s one issue of film studies that we inherit, it’s that the field went all in with the director. In film studies, directors are authors, authors are like the people who write books, and we know how to talk about books, ergo we know how to talk about film. But when you look at Hollywood as a system, who really is making Casablanca? And we all know who the artist responsible for Gone with the Wind is- that’s evident. There are other cases where I think that video games may be more like the producer-as-author than director-as-auteur. I’d be interested in hearing about World of Warcraft, which contributed to an interesting show down at the Laguna Art Museum in 2009 that Eddo curated. I got a sense of, to quote Tom Schatz’s book title from a quarter-century ago- The Genius of the System – that I wasn’t going to be looking for a single name, I was looking at Blizzard. I was looking at Blizzard’s building of something, and I don’t know who the requisite parties are, and it may be that a scholar can go in and pull out the individuals most responsible, but it was still a system.

Eddo Stern: Yeah, it’s a really tricky question because, again, we’re talking about games as one big word, and I think you would have to break it down into genres of games and, to take Blizzard as an example, we would first need to imagine where we can locate the “voice” in Blizzard’s games. Before World of Warcraft, they produced RTS’s (“real-time strategy” games), one called Starcraft and one called Warcraft. And those games are highly derivative of a board game called Warhammer 40K —it’s a direct mapping of that to the computer.

So as far as any kind of thematic originality, there you go—that’s all derivative. As far as the RTS genre, they did not invent the genre in any way—it’s been around long before that as tabletop games as well as computer games. But Blizzard is about being a very good craftsman of game design, which in Blizzard’s case is very much about subtle things like great game balance. You might get into an interesting philosophical debate about whether balance is the ultimate talent of a good game designer. Is auteurship possible within that logical system? I’ve never thought of this before, but it would be an interesting question to explore. It’s a bit different than cooking—you could say, well, cooking is similar, you know, you don’t want too much sugar in something and ruin it, so balance is very important. But you do have radical cooks who break the rules and say, “I am making a steak soup”—the new molecular gastronomy movement is messing with the boundaries of the conventional system of eating—texture, temperature, smell, color are all reimagined. In gaming, this is very difficult to achieve because the systems break down when balance is not right, and suddenly they don’t work anymore. Will Wright is a master of mapping a system. He designs like a civil engineer; his games are very carefully calibrated, there’s very little pizazz to anything he does. So is the auteurship in his case the decision at a high level to say, “I’m gonna make a game about running a city from a god’s eye perspective?” But maybe Sid Meier already did it, and this guy is just a better calibrator than the other guy. It’s really difficult within the industry model, when you have all these different genres that are constrained in different ways, to talk about auteurship. You really need to, I think, break down the question into where auteurship is located within the constraints of each genre. There’s a history for each and every game genre.

Steve Mamber: Well, that’s where one part of the problem seems to be—there isn’t quite the counterpart in video games to the extent that there’s been in film of the true independent gamer, because the ones who are interesting and at all commercial get swallowed up so quickly. Of course, there is a kind of tradition of that within film too, but you don’t have counterparts to that tier of Coen brothers-type filmmakers in video games, and I think that’s something that academia really ought to play a role in developing. They’ve talked the talk with film, but they haven’t really conceptualized it yet with video games; there needs to be this kind of independent arena for video game development that’s not avant-garde experimental (which, of course, there’s place for, too), but where there are people engaging with mainstream games enough to have an impact but not be swallowed up by EA.

Eddo Stern: You could say a game like Braid falls into that category, where it was self-produced, self-funded, and then at some point picked up by Microsoft to go on the Xbox but definitely produced without the constraints of working within a studio, developer, producer model. So there are some signs of hope.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uqtSKkyJgFM&w=560&h=315]

Steve Mamber: Yeah, maybe the early ones, the first promising ones are there, so in terms of auteurism, that’s where we should be looking.

Eddo Stern: And Rockstar could be seen as a company that is at least working within that kind of niche level where they’re definitely not trying to please every person in the gaming world. They’re making some games that are more risky in their narrative subject matter.

Steve Mamber: Well, that’s clearly the tension, yes.

Peter Lunenfeld: But again, it seems like it’s following the anonymity of the television model where there are a few recognized showrunners. We live in Los Angeles, so we tend to know more and occasionally Charlie Sheen calls one of them out, so then we really know about him. But for the most part, up until the Charlie Sheen meltdown, I was unaware that humans were actually involved in the production of Two and a Half Men — I just assumed it was an algorithm that generated scripts.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CpeQgSNB8do&w=420&h=315]

What I would say is that, unless you’re going to be someone who writes about systems, which is a communications model, you follow the extant models within a lot of film-television-art history-English departments, which have this narrative of the maker, her discourse, production, and reception. I don’t know if gaming has that or will have that, but maybe enough younger scholars digging into things will find that. There will always be people who rise up and make enough work that’s compelling enough that people will be able to discuss them in that way, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that the medium as a whole will bear the weight of auteurist discourse.

David O’Grady: That’s going to lead us into our next question as well, which we talked a little bit about, and Eddo raised this earlier, whether mainstream games are artful, or are we talking about games for the gallery, if you will—“capital A” artistic endeavors. Is there any kind of cross-pollination happening between art games and mainstream games? In particular, can we point to examples in the past or anticipate in the future when we may see influences coming from the artistic side of the aisle back into games played in the living room?

Eddo Stern: I think something really interesting is happening in the last few years in that you now have two sources of energy that come into doing interesting, radical things with games. One is the indie game movement, which is basically people using very simple tools, being highly expressionistic, generally unconstrained by things like art or politics or good taste—an exuberant sort of youthful movement of indie games. Stuff you can see at websites like TIGSource or Independent Games.

Peter Lunenfeld: Or even Adult Swim, I mean, it’s starting to pick up that influence.

Eddo Stern: Yes, the kind of quirky, off-kilter aesthetic with a little bit of music in the background and a more pop cultural, loosely collage-y aesthetic. I think that is a movement that is getting more and more presence as far as its effect on the world in institutions like the Independent Games Festival, Indiecade, and PAX, and even at GDC, people are seeing all this stuff. On the other hand, what you have way before that, but also concurrent to it, is the artist-game-hacker-modder movement that has been embraced as game art. And very few pieces of “game art” were actually games made by artists as games. They were very often re-contextualizing mainstream games or modifying game engines to do something like JODI’s super-minimalist take on Wolfenstein titled Untitled Game. Those are products of the “game art” movement which is now in decline and being replaced by the newer “indie game” movement, which, in turn, is being embraced by the mainstream gaming institutions. You also see a lot happening in academia where discussions about game studies center around the unique properties of gaming. People will argue for and say, “Well, games have to be taken on their own terms because there’s this thing called game design, a unique component of games that does not exist in other forms”. The term “Game Design“ really did not come up much in the game art and modding communities, where there was less work going into designing the game. Rather, the structural game design was taken for granted or twisted around aesthetically or thematically. A game like Super Columbine Massacre RPG, which had a very strong cultural impact, was really about taking a game design completely as it is—a kind of point-and-click adventure from the 80s and skinning it with a radically different narrative.

[googlevideo=http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=-846592551728203166&hl=en]

David O’Grady: Let’s shift from game design to distribution and access. We’ve had portable video gaming for some time, but in the last few years we’ve seen games colonize almost every portable device—they’re not physically isolated from other communication or interaction, other things that we do in our lives with these devices. This, in turn, seems to have opened up more access, lowered the threshold for entry to game designers and potentially to players as well. What are some of the major implications of the so-called casual game movement?

Steve Mamber: Well, I think there are very promising aspects to it, and it’s more on the side of production of games than what the particular platform is, because there are closed platforms, like the Nintendo DS, and there are completely open ones like Android. I guess iPhones and iPads are somewhere in the middle, where there are app stores with incredible numbers of applications, but you still kind of have to do it Apple’s way. But I think it is important that there are these kinds of possibilities for breaking out of the producer’s control of both the platforms and the games. I find very interesting websites like CreativeApplications.Net, which is supposed to highlight academic production of art, but half of the things you find there are apps that are being sold for iPhone and iPad, and to get them you have to go to iTunes, even though in many cases they’re free.

It’s just that the ways of getting this stuff out there changes significantly when people are looking at them on their handheld devices. So, I think that part of the model is moving more towards open channels of distribution that don’t necessarily involve finding an artist’s website in order to get the game. Maybe some games aren’t going to be lifelong obsessions, but I don’t think we can turn our back on Angry Birds or Cut the Rope or Paper Toss. This is a serious phenomenon, and I don’t think just a frivolous one. It’s really saying something about the ways that people enjoy games, and very quickly the ones that are popular can veer off into much more interesting things. You know Paper Toss can become Five Minutes to Kill (Yourself), or something else that’s quirky enough and interesting enough but still accessible in a way that the gallery isn’t.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=86hFt26LFIQ&w=420&h=315]

The app store is now the model, and I think it’s really great that a whole bunch of development platforms like openFrameworks have found a great deal of interest in the academic community. The openFrameworks people started doing iPhone, iPad stuff very quickly, and now there are a bunch of games that those people have done. There’s just a lot of this DIY, Open Source kind of activity that is finding a place in this mobile environment.

Eddo Stern: One thing that adds a lot of vitality to that segment of gaming is the fact that these games do cost money, but they cost so little money that the risk involved in buying a game is removed for most people. I don’t need to drop $60 on the new game and commit to a platform, et cetera, and the hours, and then the disappointment. With mobile games most folks would say, “Oh, I paid a dollar; it was good“ or “I paid a dollar; it wasn’t so good. That’s fine.” Indie game developers being paid for their craft is not a bad thing. And they don’t have to then go and work for big corporations. Zach Gage, who’s a young artist and game developer whom I was having lunch with a few weeks ago was talking about the pleasure that he’s getting out of being able to develop games for the iPad and taking his chances on supporting himself thanks to the new low-entry-point, low-risk exchange. It might seem counter-intuitive to some of us, but the fact that a game is not free will legitimize it for many people. “This game costs $5; it has more quality than some game I downloaded from an artist’s website that was free.” There’s also Steam — we could talk about Steam in the context of another more direct method of getting games, and only when Steam came online did the $10 game market really take off for people.

Peter Lunenfeld: It’s also breaking the bottleneck that we’ve talked about, from ten, twenty years ago, which was the argument about shelf space. It does engage with some of the utopian notions about the computer as a culture machine. It’s really that kind of open source distribution of bits and not stuff, and why shouldn’t it be cheap? Why should something that you can replicate endless amounts of times not be $1 or $10, why should it have to be $60? And I think there’s a really interesting cultural shift in that way. And that really comes straight out of the original iTunes store concept of, “Well, you know, I’ll spend a dollar on this song rather than just downloading it illegally.” I ask my students now—how many of them have never paid for music—and they don’t have much reason to lie. Again, the question is how many have never paid for music. Seven, eight years ago, three quarters of the hands went up in the room: “I’ve never paid a dime for any music at all.” And now you’re down to one or two kids in a class of 60 who haven’t paid for music ever.

This doesn’t mean that they pay for every piece of music, but it does mean that there is a cultural turning away from the model that completely ignore artists and copyright owners’ rights. This turn is not entirely surprising, of course, as we live in a capitalist society. But I do think that this is an interesting model—it’s not always an open, not always a free model, but it’s certainly one that I think that people are willing to participate in. A dollar a game… it’s cheaper than a glass of milk.

David O’Grady: We are running out of time, but I have one last question. No doubt many universities are grappling with how to incorporate digital media in general and video games in particular into the curriculum. If the computer has the potential to bring science and the humanities together, how do we go about the task of providing a course of study that advances video game development, scholarship, and general media literacy? How can the academy best prepare for a video game future, a future that has arguably already arrived? This is a huge question, but any impressions you might have….

Steve Mamber: I’ll do a quick one on that. This’ll start to sound a little partisan given the group, but I think there are a couple of directions that can coexist. One is that media and art- producing departments ought to be significant players in this—we should be involved in the production of games. And the other is the digital humanities route, which fortunately UCLA (thanks to Todd Presner and some others) has been very much involved in; it really is a place for collaborative activity. We’re also seeing that video games can affect the interests of a number of departments as a kind of literacy question. People should feel comfortable with video games as part of what they do, and part of what they’re studying, and part of what they’re thinking about.

Eddo Stern: As you’ve outlined here there are at least three legs. One is from a technology point of view, getting technologists involved in thinking about game technology. And then artists, whether that be writers, animators, game designers, whatever, conceptual artists, certainly the medium is offering a lot of exciting opportunities for artists of all sorts. And then, finally, from a media theory point of view it’s interesting new ground. And then after that you can imagine many intersections with other disciplines, whether it’s psychology, politics, history, media archaeology, and so on. I’m just thinking of grad students I work with here: a few from history, some from psychology, some from art history, computer engineering… it’s very diverse. I think it really would be important for institutions like ours to have an awareness of the importance of games culturally. It’s very disconcerting to see entire schools and divisions at UCLA skip a generation of hiring. There are very, very obvious holes where there’s no one working with gaming, and there won’t be for another ten years, and then we’ve missed a huge opportunity to develop the discourse in an interdisciplinary environment.

Peter Lunenfeld: The post-renaissance university, as we experience it, is around 500 years old. For, say, 350 of those years, it was ludicrous to even think about talking about contemporary culture within the university. The first English department in the United States was at Johns Hopkins, founded in 1878 and set up on a philological model, mimicking German departments, which were essentially about trying to unify German as a language through philology. So, we’re talking about just a little more than a century of humanistic engagement with the contemporary. If you’re saying, how are you going to incorporate video games in the academy, then the answer is: in fits and starts, mostly poorly, occasionally well. That’s the best we’re going to do. Because that’s the only way that we’ve been able to do it, and we’re still pretty fresh at thinking about how to build these kinds of things in an institutional context that was designed to study the past—not the present.

I did that fast! I hope I wasn’t going too long. We’ve got to go!